INTerview: Never Made (Francisco Reyes Jr.)

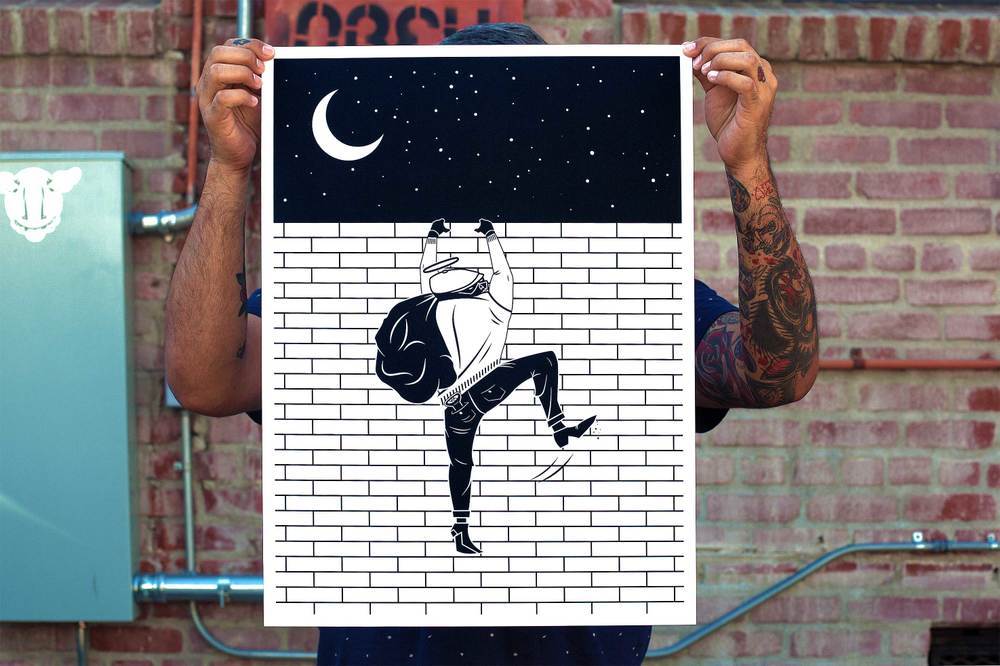

/While scrolling through my Feedly account, I came across a print release from the artist, Francisco Reyes Jr., who produces work under the name, Never Made. Francisco is a Los Angeles based Graphic Designer and Artist currently working for Obey Giant. He had just released his print, "Creepin On A Come Up", and I was instantly drawn to the subject matter and the incredible graphics. You can visit his Online Store and his Instagram to see more of his amazing work.

In an exclusive interview with Interiors, we talked to Never Made about his art and his inspirations.

INT: When did you first realize you wanted to do Art?

NM: I always liked to draw. I didn't think much of it, it was just something I found pleasure in.

I used to try to be really good at drawing as realistic as possible. I would also try to draw my favorite characters in the exact way they were drawn on the covers of comic books and on X-Men cards. I really sucked, but I didn't care! I just liked to do it.

However thinking back on it now, my dad used to take my brother and I to the video store every Friday to rent video games movies and I would always base my choice of movie or game on the cover art. I'd look for the most catchy covers and that would be my choice. Even if i had no idea what the movie was about. The cover art sold me. Meet the Feebles by Peter Jackson is one that stands out the most. My mom flipped out when she saw what I was watching and she yelled at my dad. Google it.

I've always been into visuals but I was never that good at "Fine Art." I used to be an aspiring musician. My art teacher in high school wrote in my yearbook, "Art really isn't your thing... Stick to playing guitar." When I came across Illustrator and Photoshop and learned what Graphic Design was, that was it for me. I knew that's what I wanted to do for a living. So after high school, I enrolled into design school and got my degree in Graphic Design.

I'm fortunate enough to be doing what I love for a living. It's a tough and competitive industry and I'm thankful everyday for the job I have.

INT: Favorite Art Piece/Project that you've done?

NM: My favorite art project has been definitely developing my little homie, Crispin.

I guess my favorite art "collective" that I’ve done would have to be the graphics that I did for Obey Clothing. It trips me out when I'm out and I see people in public wearing something that I designed. It's a trip.

INT: Favorite movie and why?

NM: I have a bunch, but I'll give you two. The Fountain, for sure. It's a story of eternal life, death and love, mixed in with some amazing visuals, a great story and a fucking awesome score. It's a home run in my book, and most of Darren Aronofsky’s films are. The film didn't get much love at the box office, but it's one of those gems you have to find for yourself.

My second would a French film named Jeux d'enfants (Love Me If You Dare). The visuals and cinematography are awesome and the story is really charming. I'm a sucker for movies about love, for sure.

I also love World War II movies and all the classic mobster movies, like Goodfellas, The Godfather and A Bronx Tale.

INT: How would you describe your Art to someone? What does it mean to you?

NM: Minimal with as much visual impact as I can make using a limited color palette (almost always black and white). I try to make things as simple and iconic as possible, so people can remember it. My work keeps me sane. It gets my mind off whatever tribulations are going on in my life. If I'm not working on something, I'll get super bored and just start to think too much and give myself anxiety, of which I have enough of already. It's therapeutic for me.

INT: What's your go-to inspiration? Someone/Something that you're continuously inspired by?

NM: Shepard Fairey has always been my go-to inspiration. Even before I worked for him, I was the biggest fan boy. I would study his work and couldn’t get over how iconic and powerful yet simple his work was. It was something I had always strived for in my work and still do.

I get inspired by so much. I’m very observant and anything could spark an idea in my head. For example, if I’m listening to a song that has a certain lyric that stood out to me, I'll paint a visual picture of what the lyric would look like. Then I start to brainstorm a central icon or icons and visualize typography to go along with it. I do that with pretty much everything I hear, see, and feel. Or sometimes, I just get the urge to make cool shit with no real meaning behind it. If it's aesthetically pleasing, I’m down with it.