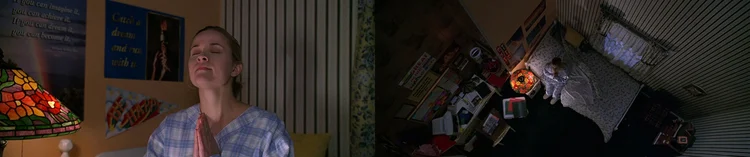

Screenshot: They Live (1988)

/"'I was blind but now I see!'" - John 9:25

"You ain't the first son of a bitch to wake up out of their dream." - Nada

Those unfamiliar with John Carpenter’s paranoid satire They Live (1988), in which a hapless, unemployed alpha-male called Nada (played by alpha-male pro wrestler "Rowdy" Roddy Piper) stumbles upon a covert alien invasion with the help of truth revealing sunglasses may, after reading that last sentence, be even less likely to seek it out.

If you scratch beneath the surface, however, the film has much to say about Reagan Era politics, capitalism, racial tensions, police surveillance and material culture -- all hot topics that were fueling the creative fire of maverick directors like John Carpenter at a time when self-preservation and social status were the mantras of the political elite. The film, according to the director himself, is as relevant now as when it was first released back in 1988:

“Well, They Live was a primal scream against Reaganism of the ‘80s. And the ‘80s never went away. They’re still with us. That’s what makes They Live look so fresh - it’s a document of greed and insanity. It’s about life in the United States then and now. If anything, things have gotten worse.”

In essence, They Live is meant to act like a wake up call to apathetic America dulled into passive obedience through mass consumerism, lured in by an all pervasive marketing assault. There are screens everywhere in the film -- from the television screens that regurgitate inane branded fluff in a seemingly endless loop, to the advertising billboards plastered around the city. The vehicles and walls in the film also act as screens to transmit messages -- lo-fi alternative surfaces used for protest by the rebel minority against the unseen elite. The various slogans, such as "thought control" and "they live, we sleep," flicker past as if interrupting a broadcast -- evidence of dissention in the ranks.

The shot featured above occurs a third of the way into the film when our reluctant hero dons a pair of the aforementioned sunglasses -- referred to by the rebels as ‘Hoffman lenses’ -- revealing a monochromatic world of authoritarian slogans as if part of a city wide culture jam. The film has essentially been stripped of its color, and so have the city's billboards been stripped of their visual enticements, leaving us with a set of functional instructions; "Submit," "Stay Asleep," "Conform," "Watch TV."

In the same manner that Dorothy entered Oz or Neo opted for the red pill in The Matrix, things will never quite be the same for Nada, and his world quickly becomes that of stark opposites: good and evil, us and them, conform or resist. In some ways, this simplified reconfiguration suits both our hero’s limited skill set and our own expectations for action movies set in the 1980s, whereby meathead protagonists fare less well in the world of emotional grey areas than they do when given a recognizable bad guy to pummel along with the necessary hardware to do so. Nada simply appropriates the Alien newspeak to his own set of instructions; "Shoot," "Kill," "Kiss My Ass, "Fuck You."

This is cinematic wish fulfillment for those in the 1980s who felt disenfranchised and disempowered to the point of despair, and a stiff middle finger to "the man" seems in hindsight the appropriate gesture to an equally simplistic mantra of "submit" by those with the power to make it happen.

The use of large scale typographic sloganeering in the film directly references work by artists such as Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger, both of whom used strategies of mass media and advertising to comment on capitalist culture in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The typeface most often associated with Kruger’s "subvertising" work -- Futura Bold -- is also the same used by John Carpenter in the film, with slight variation.

It's nearly 30 years on and it’s interesting to note how the visual look of language in They Live has been co-opted by the commercial world it was so desperately looking to undermine. The assertion made in the film is that "there is a distance between the 'lies' of commercial-ideological speech and the coercive 'truths' smuggled inside it’ -- when really, the two co-exist with relative ease. In fact, a prime example of this is how street artist Shepard Fairey’s guerilla Obey campaign of the 1990s developed into a million dollar clothing brand and his Hope poster was condoned by the official Barrack Obama campaign prior to the 2008 US Presidential Election. The artistic interventions by Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger have by now lost their initial significance as they too have succumbed to the brand strategist retrofit -- their slogans such as "I Shop Therefore I Am" and "Protect Me From What I Want" appearing on t-shirts, mugs and perfume advertisements -- social commentary, giving way to irony, giving way to ker-ching.

In fact, while protest movements will continue to use posters and banners as an effective weapon for change, their words and graphic imagery seem more likely now to end up as tomorrow’s marketing fodder, as the gap between dissent and commerce gets ever narrower.

Submit indeed.

Screenshot is an ongoing column from Gabriel Solomons, Senior Lecturer at the University of the West of England, Editor-in-Chief of The Big Picture magazine and Series Editor of The World Film Locations and Fan Phenomena book series. Screenshot examines a single shot from a film and presents an in-depth analysis.