Mutations & Megastructure: Japanese Metabolism in Akira (1988)

/With its unflinching violence and vividly rendered animations, Katsuhiro Otomo’s cyberpunk anime, Akira (1988), is an iconic cult classic. Decades after its release, this film has inspired musicians like Michael Jackson and Kanye West as well as other major Sci-Fi franchises like The Matrix (1999). While Akira continues to be praised for its richly detailed visuals and intense dystopian narrative, we shouldn’t forget the Japanese historical (and architectural) context from which so much of the film’s design comes from.

In the early 1960’s, a new architectural movement was forged within post-war Japan. Faced with the wide-scale destruction of numerous cities, a small group of architects (Kenzo Tange, Fumihiko Maki, Kiyonori Kikutake, Kisho Kurokawa, Arata Isozaki just to name a few) began to maximize and re-design the urban landscape into one of growing, modular megastructures inspired by the smallest processes of life.

A quote from their original manifesto, Metabolism: The Proposals for New Urbanism, sums up their concepts up quite nicely: “We regard human society as a vital process - a continuous development from atom to nebula. The reason why we use such a biological word, metabolism, is that we believe design and technology should be a denotation of human society. We are not going to accept metabolism as a natural process, but try to encourage active metabolic development of our society through our proposals.”

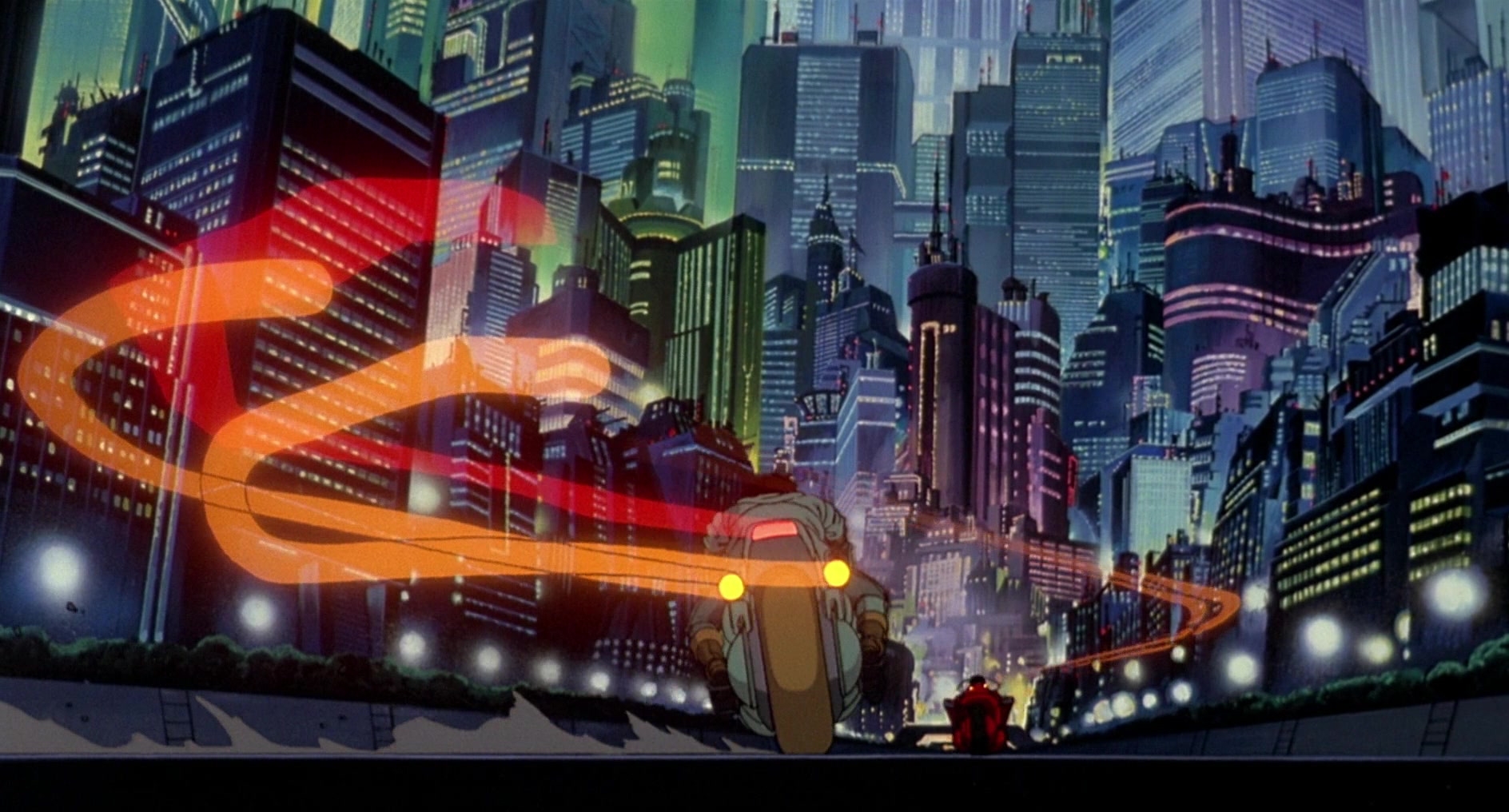

So what does a film made in 1988 have to do with an architectural movement from twenty years prior? Let’s start at the film’s opening sequence:

Kenzo Tange – Plan for Tokyo Bay, City of Ten Million (1960)

Akira’s plot is long and complex, but the film’s primary themes focus on life, death, war, and transformation. The setting -- Neo-Tokyo following WWIII -- bears a striking resemblance to Tange’s City of Ten Million. Although his proposal was supposed to serve Japan’s growing population and the resulting surge in the use of automobiles, Tange’s post-nuclear utopian model is now wrought with social unrest in Akira – protestors, biker gangs, a failing school system, and top-secret military experiments wreak havoc on the streets.

Kenzo Tange – Renewal of Tsukiji District (1963)

This is when we see the world of Akira and the beliefs of the Metabolists clash against each other. From the start of the Metabolist movement to the 1980’s, Japan underwent a period of rapid economic growth, fueled by their advances in technological innovation. Neo-Tokyo’s glittering, monolithic skyscrapers should embody this expansion, but Otomo showcases this city’s dark underbelly instead, one where the machine of living is reduced to gritty wasteland. During film’s creation, animators spent hours drawing sequences (like the one pictured above) down to the smallest individual building to heighten this sense of overwhelming, violently monstrous urban density. Neo-Tokyo becomes a place both beautiful and terrifying.

Tange’s Tsukiji District Renewal plan is a complex lattice of interconnected towers, linked together by various streets and bridges. These multi-level clusters were designed to adapt to the needs of the population. Neo-Tokyo, with its skybridges, networks of pipelines and highways, offices and apartments stacked on top of shopping malls and rooftop plazas, takes Tange’s initial plan and develops his uniform, modular design on a much larger scale. However, the city’s continuous growth – seen in scenes of construction throughout the film – don’t do very much to benefit its citizens. We see the Metabolist utopia mutate into a chaotic, unstable military state as the skyscrapers keep getting taller.

Arata Isozaki – Future City, The Incubation Process (1962)

During the film’s first motorcycle chase, we’re taken away from the shiny, neon megastructures of Neo-Tokyo to what is left of Old Tokyo. This abandoned, derelict site is crucial to Akira’s storyline (our first real introduction to the military’s top secret operations), but it’s also an important reminder of Japan’s war-torn past.

Arata Isozaki’s Future City is a place where, much like Old Tokyo, the past and future co-exist. Isozaki, having lived through the trauma of Japan during WWII, was influenced by the destruction he witnessed and decided to design a new city that would be built on top of its own ruins, a recurring cycle of life and death as the city grows and collapses.

Neo-Tokyo is not so different from Isozaki’s vision. Its highways are still attached to the city’s previous location. Although Neo-Tokyo continues to expand, the ruins of Old Tokyo remain attached to it like a shadow, a futuristic city haunted by its past.

Arata Isozaki – Re-Ruined Hiroshima (1968)

We are brought back to the ruins and the death of cities in the film’s finale as Tetsuo destroys the military’s storage facility and ravages Neo-Tokyo. Both Tetsuo and Neo-Tokyo undergo a Metabolist life cycle of their own, growing too fast and unraveling into destruction.

Kisho Kurokawa - Toshiba-IHI Pavillion (1970)

Expo 70 in Osaka, Japan would be the Metabolists’ last large-scale exposition of their architectural creations. Metabolist architects produced these monumental, futuristic pavilions by merging the construction of human cells with technological developments. Akira’s final scenes end up echoing these massive, organic structures in both shape and scope.

The Toshiba Pavilion’s simplified, spherical form doesn’t just resemble the storage structure that houses Akira’s remains as it is destroyed by Tetsuo’s psychic abilities. Tetsuo’s body begins to mutate into shapes like the Toshiba Pavilion, his powers grow increasingly unstable as his robotic arm swells into his body. He is pushed to the limit of humanity much like the Metabolists pushing their designs to the edge of architectural possibility.

After all this violent destruction, it’s fitting that Tetsuo’s mutated shape ultimately resembles a child – a symbol of the life and death cycles now tangled in one another.

In Akira, we see the boundaries between human and machine become blurred. Tetsuo’s body develops into a mutated megastructure of its own, taking the Metabolist growth process to absolute extremes. It’s no surprise that Tetsuo meets his end within an Olympic Stadium (Toyko was the host of the Summer Games in 1964) – the ultimate symbol of Japanese reconstruction now left in ruins:

Kenzo Tange – Yoyogi National Gymnasium (1964), used during the Olympics for smaller events.

Akira is not only a sci-fi, dystopian masterpiece. This futuristic anime grapples with the complexities of Japan’s post-war reconstruction, from Tokyo’s rapid economic growth to the resulting social unrest. Otomo has talked about this tension as his main source of inspiration for the film in previous interviews when, in the 60’s, he watched homeless youth and political demonstrators litter the streets in search of change.

While it’s unclear if Otomo pulled all his architectural influences directly from Metabolist projects, the Metabolists themselves were also witnesses to Japan’s recovery and took part in the societal questions raised during this era of recovery. Their futuristic city designs examined the needs of the human body, the very processes of life needed for it to grow. Their designs focused primarily on organic megastructures, constructed to change with society.

Akira presents a world where the Metabolist utopia has failed. Although set within a fictional future, the film examines Japan’s period of reconstruction. These megastructures of life -- from Tetsuo’s psychic abilities to the bright Neo-Tokyo skyscrapers – mutate into chaos. As the viewer, we are placed within the cycle of life and death, forced to witness a future that grows over its ruins and destroys itself all over again.